Are coercive control laws the answer for victims without a bruise?

Domestic abuse is not always an incident of violence, there is not always a point of crisis.

It can be silent, a pattern of behaviours used to control, intimidate, create dependency and render victims powerless.

It can be as invasive as a flood of phone calls.

It can be as demeaning as constant surveillance.

It can be as harrowing as sabotaged employment.

Given the umbrella term "coercive control", this behaviour is used to strip away a person’s identity, according to Stopping Family Violenc sector development manager Kate Jeffries.

While coercive and controlling behaviour has always been a major part of abusive relationships, Ms Jeffries says it is quite new to the community conversation about domestic abuse.

“Coercive control can include physical violence, psychological violence, financial abuse and all the things we already know about, but it’s those plus more,” she says.

"It's all the underlying things that are really hard to identify, it's the things that strip away a person's autonomy."

Across Australia, there are a number of investigations into the impacts of coercive control and whether it should be criminalised.

In WA, the work is being led by the Office of the Commissioner for Victims of Crime.

As WA's peak body in perpetrator response, Ms Jeffries says Stopping Family Violence is not in favour of criminalising the behaviour until there are adequate resources to support it.

In 2016, legislation was created in WA requiring courts to refer suspected or definite perpetrators of domestic abuse to behavioural change programs.

However, Ms Jeffries says the legislation is ignored in many cases because of limited spots, long waitlists, and some programs are located hours away from where the perpetrators live.

Last year, the act of suffocating an intimate partner, known as non-fatal strangulation, was criminalised in WA.

This legislation has since fallen short, according to Jeffries, with many first responders such as ambulance staff receving little or no training on what to look for when arriving to a scene of a possible strangling.

Ms Jeffries says training is essential to ensure we are identifying the perpetrator correctly. At times, victims are arrested as the person of interest without contextualising their behaviour as ‘acts of resistance’ to the violence and abuse they experience daily.

“Police are trained to attend a call out and view evidence at that point in time. This is incident based work. Police have commenced the introduction of a perpetrator patterned based approach to their investigations," she says.

“There needs to be increase training and support for Police and Court systems to stop victim-survivors being incorrectly identified as the perpetrator of family and domestic violence.”

WA criminal lawyer Natasha Stewart also does not believe coercive control should be criminalised due to the difficulty in gathering evidence.

Ms Stewart says she regularly sees Violence Restraining Orders (VRO) be awarded on disingenuous or flimsy grounds.

With cases becoming broader and more common, she fears coercive control legislation would deepen the issue.

“At this point I have restraining order fatigue,” she says.

“It’s tricky to bring in such broad concepts when psychological abuse is already so hard to prove.”

Natasha Stewart, Western Australian Criminal Lawyer.

Tasmanian Family Lawyer, Oona Fisher. Photo provided from FitzGerald and Browne Lawyers.

Tasmanian Family Lawyer, Oona Fisher. Photo provided from FitzGerald and Browne Lawyers.

Since 2004, Tasmania is the only jurisdiction in Australia that addresses coercive and controlling behaviours with two offences targeting economic abuse and emotional abuse.

In February, Tasmania's Office of Public Prosecutions made a submission to the New South Wales Committee on Coercive Control, detailing how the laws have played out.

The submission reported that since the legislation's introduction, numbers of prosecutions had been low.

This result was attributed to the high bar set for prosecutors, with some first-time cases dismissed because it must be proven the abuser had known their behaviour was emotionally or economically abusive.

In practice, Tasmanian family lawyer Oona Fisher says coercive control offences tend to become pieces within the context of Family Violence Orders.

She says while she doesn’t know if these offences ultimately settle a case, they have played a role helping women make sense of their stories and normalised the conversation around it in the court room at the very least.

Ms Fisher says evidence collection is getting easier with improving technology and other submissions have shown rates of emotional abuse charges have increased since 2004, with none laid in the three years following and 186 by the end of 2019.

WA Ruah Community Services family and domestic violence general manager Tanya Elson welcomes WA implementing similar laws, so long as resources to educate the wider community shape up.

Ms Elson says she knows there are women who will not recognise their experience as domestic abuse.

She recounts conversations in hospital rooms with physical violence victims who have no clue coercive and controlling behaviour is a form of abuse.

Ruah Community Services provides accommodation for women and their children relative to their risk of being killed, but Ms Elson knows there are many women who will never be hit, but the abuse they endure every day is appalling.

Tanya Elson, General Manager of Family and Domestic Violence services at Ruah Community Services. Photo by Harmony Romsloe.

Tanya Elson, General Manager of Family and Domestic Violence services at Ruah Community Services. Photo by Harmony Romsloe.

“I think part of our conversation about coercion and control and understanding different types of violence, is that it isn’t a hierarchy in which there needs to be a crisis,” she says.

Police are not necessarily needed when the abuse is not a physical crisis, but the resources to connect women to information are essential, Ms Elson says.

Two years of research in Western Australia – backed by former WA Chief Scientist Lyn Beazley – found resources were lacking for domestic abuse victims who were not at a point of crisis.

Your Toolkit website

Your Toolkit website

Original patrons of Your Toolkit: including Western Australia's former Chief Scientist Lyn Beazley (second from the left).

Original patrons of Your Toolkit: including Western Australia's former Chief Scientist Lyn Beazley (second from the left).

Your Toolkit's first-step resources for victims of domestic abuse.

Your Toolkit's first-step resources for victims of domestic abuse.

In response, WA not-for-profit organisation Financial Toolbox launched Your Toolkit, an online resource which contains a roadmap of information for women to leave an abusive situation at any level and get into financial independence.

Financial Toolbox was created in 2015 after a gap was noticed in the financial literacy of women compared to men.

The organisation started targeting the problem with community education workshops, before launching Your Toolkit in 2020 for women experiencing abuse.

Your Toolkit general manager Penny Fegan says women at risk of abuse can benefit from financial education to support their independence.

“The number one reason women return to an abusive relationship is because they are not financially stable on their own." she says.

“Part of the abuse is often cutting off or controlling finances.”

Ms Fegan says while abuse in relationships may not always be obvious, the red flags are there.

Your Toolkit’s strength lies in its ability to extend help to the women who may not even identify themselves as victims of abuse, yet feel things are not quite right and want to make a change, Ms Fegan says.

The resources serve as portals to connect victims to help and education, but ultimately the burden should not fall on the victim, according to Ruah's Tanya Elson.

“The onus should be on us as a community to be recognising when men are perpetrating violence, when women are experiencing abuse and when we are doing things to condone it. We all have a responsibility to try and understand what we’re seeing and to know what supports are available.”

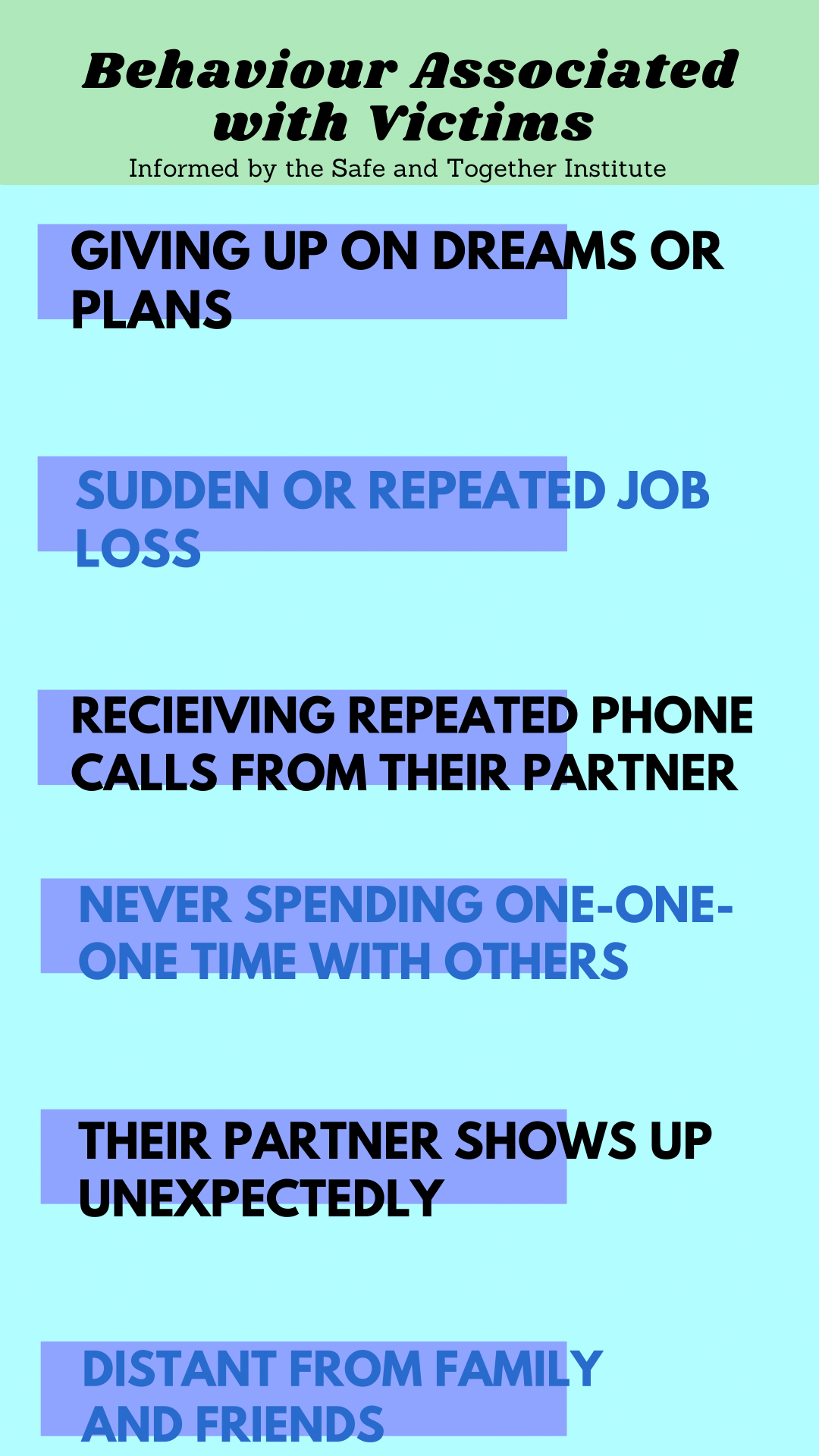

Sharing this sentiment, Kate Jeffries from Stopping Family Violence points to the Safe and Together Institute and Insight Exchange resources on how to effectively respond and ally with domestic abuse victims.

As for coercive control criminalisation, Ms Jeffries says WA is not ready yet and that it may just become another piece of legislation without the resources to support it, a quick fix instead of a broad system overview.

Infographics made by Harmony Romsloe, informed by Safe and Together

Infographics made by Harmony Romsloe, informed by Safe and Together

Family and Domestic Violence support services:

If you need help immediately call emergency services on 000

· 1800 Respect National Helpline: 1800 737 732

· Women’s Crisis Line: 1800 811 811

· InTouch Multicultural Centre Against Family Violence: 1800 755 988

· Men’s Referral Service: 1300 766 491

· Mensline: 1300 789 978

· Lifeline (24-hour Crisis Line): 131 114

· Relationships Australia: 1300 364 277