Cutting the line

The fight to end shark fishing in Indonesia

The boat skims across turquoise water, its diesel engine roaring through the tranquillity as waves slash against the hull.

The inside of the cabin is perfumed with the concoction of cigarette smoke, engine fumes and salt spray.

The paint on the walls is chipped, cracked and crusty.

A fishing lure hangs from a rusted hook, rocking to the rhythm of the roll.

The drone of the engine floods the cabin, muffling all conversations with its din.

Only one sound can break through the engine’s rumble - laughter, erupting from within.

Australian conservationist Maddison Stewart does not speak Bahasa, and her crew do not speak much English.

But they do not need to talk.

The laughter makes it clear.

These are her people.

To some, Maddison goes by a different name -“Shark Girl”.

The 29-year-old from Queensland is one of the world's most prolific shark protectors. Her filmmaking earned her the title of 2017’s Australian Geographic's Young Conservationist of the Year.

In 2018, Maddison began working with Odi Pratama, a multi-generational fisherman from Lombok, Indonesia. With Odi and his crew, she created Project Hiu.

"Hiu" in Bahasa means "shark".

The Project helps fishermen transition to tourism, taking their hooks out of the ocean, keeping fishermen with their families, and saving sharks in the sea.

The income Project Hiu earns from eco-tourism is used to employ the men and rent out their boats.

The fishermen can earn more money from sharks, Maddison says, but they choose to fill their boat with tourists instead.

Shark fishers spend up to two weeks at sea filling their boat with up to 100 sharks.

Shark fishers spend up to two weeks at sea filling their boat with up to 100 sharks.

Pratama 01 is transitioning to eco-tourism after a long history of shark fishing.

Pratama 01 is transitioning to eco-tourism after a long history of shark fishing.

Today, the deck is packed with sightseers, snorkel gear, and swimwear hanging up to dry.

Not long ago, the deck was filled with blood.

Fishing lines

Hooks

And death.

The crew once hunted sharks, slaughtering hundreds yearly for the value of their fins.

Indonesia's shark fishing industry plays a vital role in the international shark fin trade, helping to ensure a constant supply of shark fin soup flows through the lucrative Chinese market.

International shark fin exports are valued at more than $US438 million ($AU673 million) according to a 2021 'Management of Shark Fin Trade To and From Australia’ report, released by Humane Society International Australia, the Australian Marine Conservation Society, and the Environmental Defenders Office.

Indonesia is listed as one of the largest exporters of shark fins, according to the report.

The Indonesian government does monitor shark fishing, however, according to conservation news platform Mongabay, there is a significant lack of oversight in the monitoring, allowing illegal exports to run "rampant".

An entire shark can be sold for around 1.2 million rupiah ($AU80) in Indonesia, but when the fins are removed and processed, a kilogram of shark fins can be sold for $AU2,000 in Hong Kong.

Despite the disparity, for the fishermen of Lombok, who catch up to 100 sharks in a single two-week fishing voyage, it can be a high-paying job.

However, Maddison says, it’s environmentally and economically unsustainable.

“There has been a 70 per cent decline in shark populations globally over the past 50 years,” Maddison says.

A 2013 paper published in scientific journal Marine Policy, estimates between 6.4 per cent and 7.9 per cent of global shark populations are killed annually.

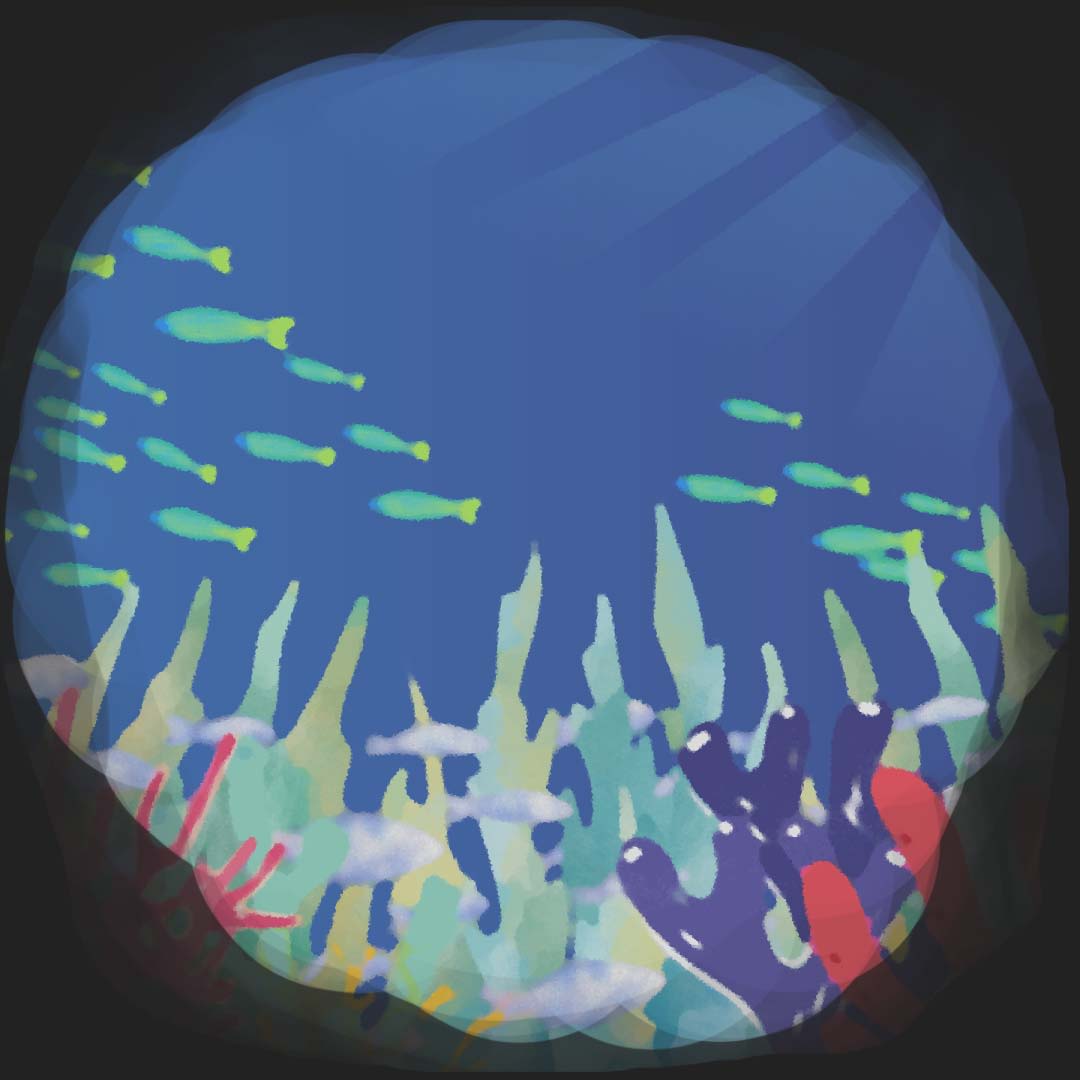

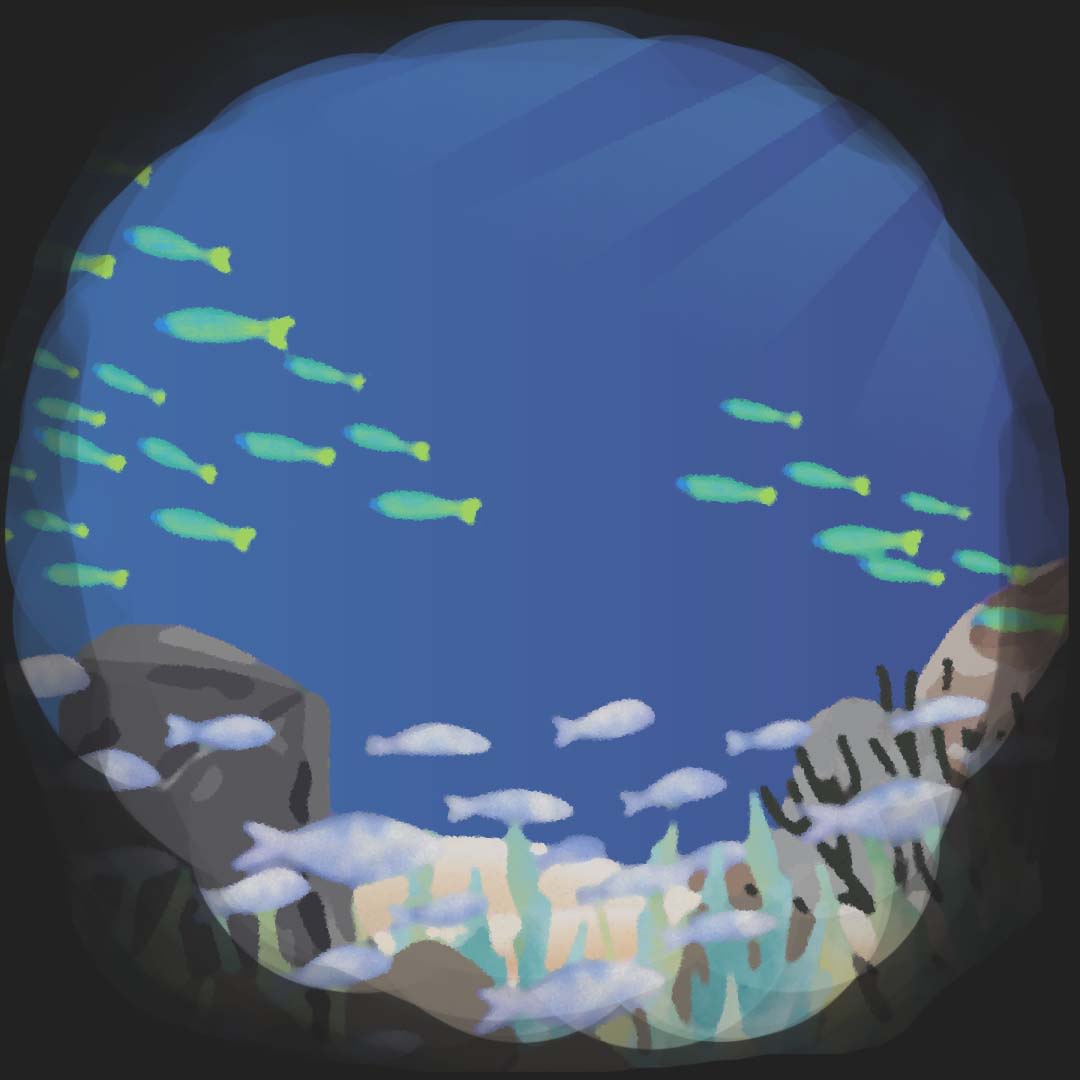

Ocean ecosystems aren’t limited to cultural borders.

Indonesia's ecosystem shares many characteristics to Australia’s northern waters, Australian marine biologist Jake Cherry says.

He says if too many sharks are killed in Indonesian waters, there is a high chance imbalances in the ecosystem will careen out of control.

“If sharks are fully removed from the ecosystem, it would be chaos," he says.

“You’re taking out a key apex predator and [apex predators] keep food webs in check everywhere.

“When you remove a link like [sharks], everything below is left to thrive out of control.

"When fish grow out of control, everything below them in the food chain gets eaten to extinction.”

As apex predators, sharks maintain ecosystems.

As apex predators, sharks maintain ecosystems.

Without sharks, smaller species can explode in numbers.

Without sharks, smaller species can explode in numbers.

Unchecked, smaller fish can decimate their food sources.

Unchecked, smaller fish can decimate their food sources.

Entire reefs can die without sharks.

Entire reefs can die without sharks.

Away from the hum of the engine, Maddison tells a group of tourists about a fishing voyage that almost went tragically wrong.

“Manan was nearly killed when a hammerhead dragged him into the water by a hook through his hand,” she says.

He was dragged 20 meters underwater, with only brief moments to gasp for air before being dragged into the abyss.

He was pulled under, over and over, until the line finally snapped.

Afterwards, Manan said he thought he would die.

“He only thought of his family, and who would take care of them if he was gone,” Maddison says.

“Amongst my crew, there have been two deaths and one loss at sea. It’s clear that shark fishing is an incredibly dangerous occupation.”

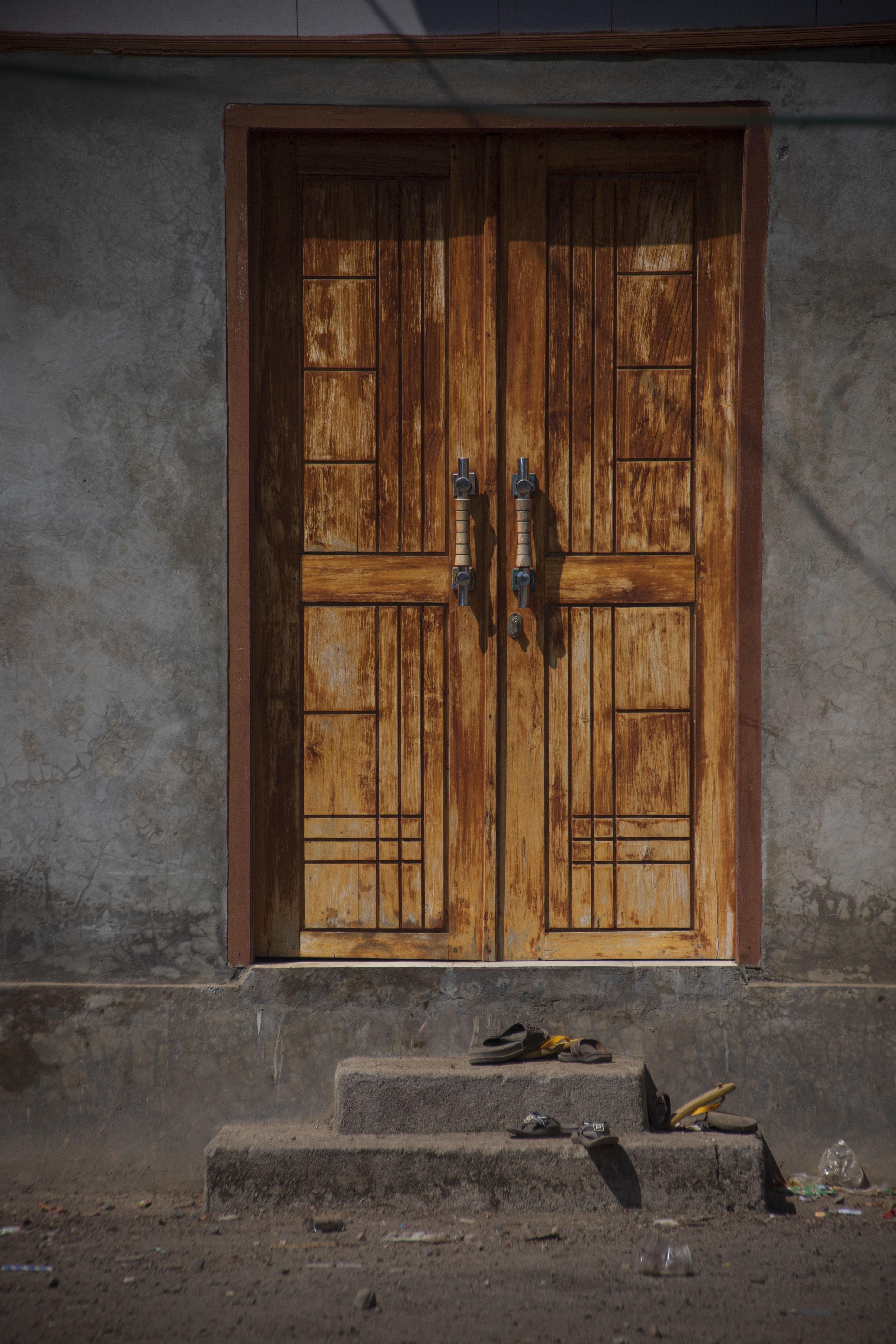

Conditions in the village are cramped and job opportunities are limited.

Conditions in the village are cramped and job opportunities are limited.

The engine dies down and the boat pulls dockside.

Maddison leads the tourists through the overcrowded island village the fishermen call home.

The cramped village, a 20-minute boat ride from Lombok island, is a twisting maze of tight-knit houses with cats, goats, and chickens rambling through.

The visitors are welcomed into the home of one of Maddison's crew.

A lone fan battles against the humidity.

The men sit, filling their lungs with cigarette smoke, as the fan forces the drafts into the entry.

The group are engulfed in the cloud but the fan stays on.

They would rather choke than swelter.

Sitting in the tiled entry, the group of tourists circle local teacher Ibu Muhibba as she shares her experience of life on the shark-dependent island.

Muhibba has one of the few jobs on the island that keeps her out of the ocean.

It is a job that she loves because everyone in the world has had a teacher and people will always need them, she says via a translator.

“People can’t succeed without teachers,” she says.

Her son is currently at university in Lombok and she says it would be a blessing for him to get a job on the mainland.

There are no opportunities on the island, beyond the dangers of shark fishing.

“Here, you work as a fisherman or as a teacher, that’s it," she says.

“As long as it’s not fishing, my family will try anything.”

Maddison shares Muhibba's belief that education is vital to ending the generational dependence on fishing.

Teacher Ibu Muhibba believes education is key to improving life in the village.

Teacher Ibu Muhibba believes education is key to improving life in the village.

One of Project Hiu’s main goals is to improve the village’s school, Maddison says. The Project has provided classrooms with air conditioning, built toilet blocks and are building a rainwater tank so the school children have access to fresh water.

Mention of Project Hiu causes Muhibba’s face to light up and she does not need her translator to express her gratitude.

“Thank you, very much, for all."

By 2033, shark-based eco-tourism will be worth more than $US785 million ($AU1.2 billion), according to the Humane Society's 'Management of Shark Fin Trade To and From Australia’ report.

For Maddison's crew, there is still a long way to go before their fledgling eco-tourism venture has the same short-term financial rewards as shark fishing, but it is a choice they are willing to make.

Tourism can be unreliable and the men face being forced to return to the dangers of shark fishing to support their families.

Her dream of having a fleet of 13 ships is slowly becoming a reality.

For Maddison and the 14 men employed by Project Hiu it will be a difficult journey, but Maddison is determined to see it through.

“No one has treated these men like the good men they are,” Maddison says.

“Not enough conservation is approached with compassion.”